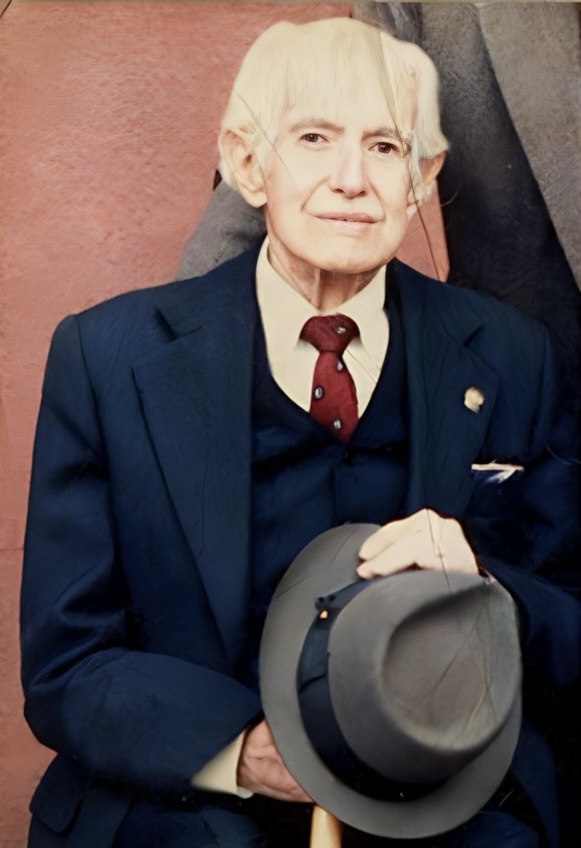

Ángel Leónidas Araújo Chiriboga (Riobamba, October 21, 1900 – Quito, February 15, 1993) was a figure of remarkable versatility and profound influence within Ecuador’s cultural landscape. His diverse career spanned composition, poetry, public service as a tax inspector for the Ministry of Finance, hotel management, and a notable tenure as editor-in-chief of the Estampa de Bogotá magazine, but it was his indelible contributions to the pasillo genre that cemented his legacy. This article explores the life and works of this distinguished Ecuadorian artist, whose talents bridged the realms of music and literature, leaving an enduring mark on his nation’s cultural heritage.

Early Life and Education

Born in Quito on October 21, 1900, Ángel Leónidas Araújo Chiriboga hailed from a distinguished lineage, the son of Colonel Don Ángel Felipe Araújo y Ordóñez—a prominent figure in Riobamba (1868 – Quito 1916) known for his roles as a writer, poet, President of the Cantonal Council of Guaranda, Governor of Chimborazo, Undersecretary of the Ministry of Government, deputy and senator on several occasions, Minister of the Court of Accounts in Quito—and Obdulia Elisa Chiriboga y Gonzáles. The family soon relocated to their ancestral city of Riobamba, which profoundly shaped Araújo Chiriboga’s artistic outlook. Amidst a bustling household of several siblings, he soaked in the cultural and natural essence of his environment. His formal education at Riobamba’s San Felipe and Maldonado schools further nurtured his emerging talents in literature and music. Araújo Chiriboga was not the only artist in the family; his brother, Jorge Araújo Chiriboga, also made his mark as a poet and composer, underscoring a rich familial legacy of artistic contribution.

Career and Interests

From an early age, Leonidas Araujo exhibited a precocious talent for music and poetry, composing his first song at thirteen. His early career was characterized by active participation in the literary scene, founding the magazine Acuarela alongside fellow writers Ángel León and Gerardo Falconí in 1918. His work garnered recognition, including an Honorable Mention from El Telégrafo in 1923 for his poem “Muerta.” His poems found audiences in various prestigious publications, such as the newspaper Los Andes de Riobamba, and in the magazines Ensayos, Savia, and Semana Gráfica of Guayaquil, further establishing his reputation.

His musical journey was equally distinguished. He was a central figure in promoting the pasillo, a genre deeply intertwined with Ecuadorian identity. Leonidas Araujo’s compositions, such as “Rebeldía” and “Almas Gemelas,” were performed by iconic singers, including his sister-in-law Carlota Jaramillo, known as the alondra ecuatoriana (Ecuadorian lark). His influence extended beyond his own compositions as he inspired and collaborated with other musicians, solidifying the pasillo’s place in the nation’s heart.

The Legacy of “Rebeldía” (Defiance)

In the heart of Ecuador, a piece of music emerged that would forever alter the cultural landscape and challenge ecclesiastical authority. Composed by Ángel Leonidas Araujo Chiriboga, a native of Riobamba, “Rebeldía” became a symbol of defiance against the stringent orthodoxies of the time. This pasillo, later tagged as “cursed” by the Catholic Church, was not just any composition; it was a clarion call that resonated with many Ecuadorians, questioning the harsh decrees of fate ascribed by divine will.

The story of “Rebeldía” is intricately tied to the socio-religious context of Ecuador in the 1920s and 1930s, a period marked by the influence of Monsignor Carlos María de la Torre. Occupying the Episcopal Chair of Riobamba, de la Torre was renowned for his ultra-conservative and intolerant stance, often clashing with the city’s political, civil, and educational institutions over his ultramontane ideology. His tenure saw a dogmatic adherence to Catholic doctrine, leaving no room for deviation or dissent—even from popular culture and music.

Araujo Chiriboga, already known for contributing some of the most popular pasillos to Ecuadorian music, including the historically significant “Amor grande y lejano”—the first song recorded in Ecuador at Radio “El Prado,” performed by Carlota Jaramillo—would soon find himself at the center of controversy. “Rebeldía” scandalized Monsignor de la Torre, leading to an unprecedented ecclesiastical decree that sought to silence its creator, performers, and even listeners, with threats of excommunication. The bishop’s condemnation was rooted in the perception of the song’s lyrics as a direct challenge to the infallibility of divine judgment, deemed heretical for questioning God’s immutable order.

However, the attempt to suppress “Rebeldía” had the opposite effect, igniting a surge of interest across Ecuador. Far from being silenced, the song found its way into bars, taverns, and public gatherings, becoming a vibrant symbol of resistance. Its widespread adoption across social strata underscored not just its universal appeal but also the collective yearning for a voice in the face of dogmatic oppression. The very act of performing or listening to “Rebeldía” became an act of defiance, transforming the pasillo into a piece celebrated throughout Ecuadorian society.

Through “Rebeldía,” Ángel Leonidas Araujo Chiriboga did more than contribute to the rich tapestry of Ecuadorian music; he etched his name into the annals of cultural history as a figure of artistic freedom and expression. The song’s legacy, marked by its journey from condemnation to celebration, highlights the enduring power of music as a form of social commentary and resistance, reflecting the spirit of a nation poised for change.

REBELDÍA

Señor no estoy conforme con mi suerte

Ni con la dura ley que has decretado

Pues no hay una razón bastante fuerte

Para que me hayas hecho desgraciado

Te he pedido justicia te he pedido

Que aplaques mi dolor calmes mi pena

Y no has querido oírme o no has podido

Revocar tu sentencia en mi condena

Casi nada te debo no me queda

Sino un amor inmensamente triste

Ya saldare mis cuentas cuando pueda

Devolverte la vida que me diste.

DEFIANCE

English Translation of "Rebeldía" by Richard Gabela, April 2, 2024.

Lord, I am not content with my lot

Nor with the harsh law you’ve decreed

For there isn’t a reason strong enough

For you to have made me miserable.

I have asked you for justice, I have pleaded

For you to soothe my pain, to ease my sorrow

And you have neither wished to hear me nor been able

To revoke your sentence in my condemnation.

I owe you little, nothing is left for me

But a love immensely sad

I will settle my accounts when I can

By returning to you the life you gave me.

Rebeldía (Spanish)

Señor no estoy conforme con mi suerte

Ni con la dura ley que has decretado

Pues no hay una razón bastante fuerte

Para que me hayas hecho desgraciado

Te he pedido justicia te he pedido

Que aplaques mi dolor calmes mi pena

Y no has querido oírme o no has podido

Revocar tu sentencia en mi condena

Casi nada te debo no me queda

Sino un amor inmensamente triste

Ya saldare mis cuentas cuando pueda

Devolverte la vida que me diste.

Rebeldía (Defiance, English Translation)

Lord, I am not content with my lot

Nor with the harsh law you’ve decreed

For there isn’t a reason strong enough

For you to have made me miserable.

I have asked you for justice, I have pleaded

For you to soothe my pain, to ease my sorrow

And you have neither wished to hear me nor been able

To revoke your sentence in my condemnation.

I owe you little, nothing is left for me

But a love immensely sad

I will settle my accounts when I can

By returning to you the life you gave me.

Literary Career and Accolades

Leonidas Araujo ’s literary output was significant, with poems that were often set to music by prominent Ecuadorian composers. His work explored themes of love, nostalgia, and the beauty of the Ecuadorian landscape. His collection of poems, Huerto Olvidado (First published in Riobamba, 1945; Second Edition, 1977), and his autobiography (1988) stand as testaments to his reflective and introspective nature. Throughout his life, he received numerous accolades and honors for his contributions to Ecuadorian arts and culture. He was honored multiple times in his province by both the Cantonal Council and the Casa de la Cultura Núcleo Chimborazo. He also served as the President of the Society of Artists and Composers of Chimborazo, demonstrating his leadership and influence in his local artistic community.

Four Decades in Colombia

Leonidas Araujo spent an extensive period of his life in Colombia, where he lived for about forty years. His time there was marked by significant professional contributions, notably as the editor-in-chief of the magazine Estampa of Bogotá. This role allowed him to remain engaged with the literary and cultural milieu, even while away from Ecuador. In addition to his editorial work, he continued to compose music, with his pieces finding new audiences and performers in Colombia. This chapter of his life reflects his enduring commitment to the arts and his ability to influence and participate in the cultural scenes beyond his homeland. He returned to Ecuador in 1974.

Legacy

Leonidas Araujo’s legacy is multifaceted. As a composer and poet, he played a crucial role in the evolution of the pasillo, imbuing it with a lyrical depth that resonated with the Ecuadorian spirit. His works continue to be celebrated and performed, testament to their enduring appeal. Moreover, his life’s work as an artist, public servant, and cultural promoter highlights a dedication to enriching Ecuador’s cultural landscape.

Reflections

Ángel Leónidas Araújo Chiriboga’s journey from a young poet and composer in Riobamba to a revered figure in Ecuadorian culture underscores a life dedicated to artistic expression and cultural enrichment. His compositions and poems not only enriched the pasillo genre but also captured the essence of Ecuadorian identity, making him a pillar of his country’s cultural heritage. Through his music and words, Leonidas Araujo crafted a legacy that continues to inspire and move the hearts of Ecuadorians.

Works

- Huerto Olvidado (Riobamba, 1978)

Anthologies

- Antología de poetas Riobambeños (Riobamba, Ecuador: Imprenta Municipal, 1963)