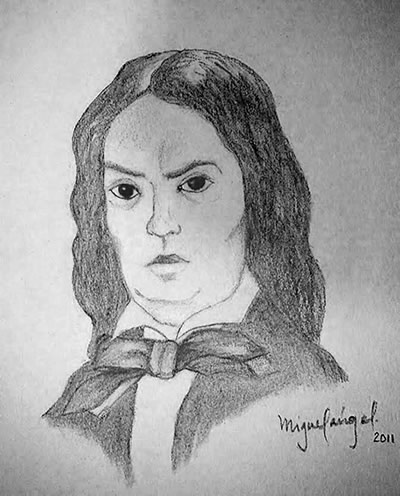

Felix Valencia Vizuete (Latacunga, August 31, 1886 – Quito, January 3, 1919) was an Ecuadorian poet often called the “Poet of Sorrow.” During his lifetime he published the books “Cantos de vida y muerte” [Songs of Life and Death] (1911) and “La epopeya de San Mateo” [The Epic of Saint Matthew] (1914). In 1934, his friend, writer and journalist Alejandro Andrade Coello, published “Los poemas del dolor” (Poems of Sorrow), a posthumous collection of his poems. Valencia’s life and work were marked by loneliness, misanthropy and melancholy.

Introduction

Félix Valencia Vizuete was born on August 31, 1886, in Latacunga, Ecuador, to Pedro Valencia and Dolores Vizuete, both natives of the town. The untimely loss of his parents left Félix to face life alone. Despite limited finances, Félix received his primary education in Latacunga and later attended Colegio Mejia in Quito for his high school studies (graduating in 1908). Valencia’s existence became characterized by profound loneliness, misanthropy, and an overwhelming sense of sorrow, positioning him as a representative figure of Ecuador’s renowned “Generación Decapitada” (Decapitated Generation).

The Poet of Sorrow

Félix Valencia is celebrated as one of the most remarkable poets of the turn of the century. Possessing an existentialist, sentimental, and proud disposition, he crafted verses that embodied dreams and romance, while also conveying the depths of sorrow and expressing protest against the prevailing poverty and sadness of the era.

As a societal outcast, Valencia’s poetry effortlessly oscillates between the realms of tragedy and sublimity. His verses are adorned with vivid imageries of candles and crows, vultures and ghosts, as if the specter of death ceaselessly pursued him. His dreams were entwined with the mysterious realms of Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire, Barbusse, and Count Lautreamont. In Quito’s Plaza Grande, curious onlookers observed Félix’s pensive and aloof demeanor, draped in a weathered black garment, almost verdant from years of use, with his long hair cascading over his strong shoulders. Gossipy whispers trailed him as he strolled through the streets, sometimes accompanied by a loyal dog, en route to the La Madgalena neighborhood. Some labeled him a poet, while others dismissed him as a bohemian or a vagabond.

Published Works

Despite his limited resources, Félix Valencia self-published two booklets of verse. One showcased his epic inclinations, eulogizing the heroic deeds of Ricaurte in San Mateo, while the other, titled “Cantos de Vida y Muerte” (Songs of Life and Death), unveiled his lyrical prowess.

A facet of Valencia’s poetry that has received insufficient exploration is his affinity for classical verse. While it is true that some of his compositions possess unfinished phrases, he nevertheless achieved extraordinary, refined, and flawless metrics. His predilection for classical meters is evident, particularly his fondness for the eleven-syllable line. Works like “Mar Adentro” and “La Gran Mentira,” along with the entire “Epopeya de San Mateo,” adhere to this metrical pattern. Additionally, Valencia ventured into the realm of the sixteen-syllable line, employing two hemistichs of eight syllables each. Only the poem “Calvario,” featured in the “Epopeya de San Mateo,” deviates from these patterns, embracing a free verse-like structure.

Félix Valencia’s Lost Corpse

Félix Valencia, working at the “San Juan de Dios” Hospital in Quito, adopted the guise of a patient with the knowledge and assistance of a sympathetic physician. This arrangement allowed Félix to stay at the hospital, providing him with shelter in exchange for his assistance in various duties. However, this seemingly beneficial agreement took a tragic turn. Félix contracted typhoid fever and, on January 3, 1918, he passed away at the age of 33. Following his untimely demise, his lifeless body was transported to the morgue but mysteriously disappeared without a trace.

Numerous speculations circulate regarding the fate of the poet’s remains. One suggests that during the grieving process, the mourners of another deceased individual, who coincidentally passed away on the same day as Félix Valencia, mistakenly took his body and interred it in an unknown location. Another, more macabre and almost reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno, insinuates a vile trade in human cadavers. During that time, bodies were exhumed shortly after burial, subjected to a slow and gruesome cooking process until reduced to pork cracklings, and then sold as cheap sandwiches, garnished with lettuce and bread. It is said that Félix Valencia’s body met this ghastly fate.

Legacy

In his hometown, Félix Valencia’s memory is honored through the dedication of a street, a new urban development, and a school bearing his name. In 1924, the Literary and Musical Center “Félix Valencia” was established in Quito, preserving his legacy. In 1934, a pamphlet titled “Los poetas del Dolor” (The Poets of Sorrow) circulated, featuring his poetry and accompanied by a prologue penned by Alejandro Andrade Coello. In 1966, the “Galaxia” Literary Group in Latacunga erected a cenotaph in his memory at the General Cemetery. As a posthumous homage, his poem “Mar adentro” was set to music by composers Carlos Amable Ortiz, Humberto Dorado, and Miguel Ángel Cásares, and was popularized by the Benítez and Valencia duo.

The Decapitated Generation

Félix Valencia Vizuete, born on August 31, 1886, in Latacunga, Ecuador, has been recognized by certain scholars as belonging to the “Decapitated Generation” due to the similarities between his poetry and the style of that literary movement. His life bears witness to the pain, madness, and despair characteristic of that generation. However, despite being a contemporary of renowned figures such as Medardo Ángel Silva, Noboa y Caamaño, Arturo Borja, and Humberto Fierro, Félix Valencia remains relatively unknown in comparison.

Poems

LA GRAN MENTIRA

Cristo y Judas son flores de heroísmo

y la una sombra agranda la otra lumbre;

si Cristo es grande como toda cumbre,

Judas es negro como todo abismo.

Mas los dos por extraño fatalismo,

al predicar amor y mansedumbre,

el uno es presa de ebria muchedumbre

el otro es verdugo de sí mismo.

Mientras tanto el Dios hombre y el suicida,

hasta hoy no pueden con sus muertes rudas

disminuir las miserias de la vida.

¡Y entre tantos horrores no se ha visto

un acto más infame que el Judas,

ni un morir más inútil que el de Cristo.

TUS OJOS

Ojos negros, nostálgicos, que yerran,

en busca del amor con que se halagan;

ventanas que al amado no se cierran

y estrellas que al ungido no se apagan.

Ojos negros, pletóricos de duelos,

que tenéis para el mal que os hace estragos.

La eterna mansedumbre de los cielos

y la eterna tristeza de los lagos.

Ojos negros, dolóricos, que a solas

veis en el llanto de tus cuencas llenas,

la eterna turbulencia de las olas

y la eterna borrasca de las penas.

Ojos negros, sedientos de ternuras,

que lleváis en el fondo de sí mismos,

el eterno fulgor de las alturas

y la eterna abstracción de los abismos.

Ojos negros, que tanto os amo y os admiro

cuando desmaye mi vida atribulada,

enviadme entre las alas de un suspiro,

la dulce caridad de una mirada.

Works

- Los poemas del dolor (1934)

- Cantos de vida y muerte (1911)

- La epopeya de San Mateo (1914)